Separate but Special: Overrepresentation of minority students in special education in America’s most diverse city

By: Elena Rein

On the first Friday evening of every month, something amazing happens in downtown Oakland. Artists from around the city set up their work, galleries open their doors, food trucks line the taped-off streets and every few blocks a different band blasts their original music. This is a place of extraordinary diversity: of thought, of lifestyle, of artistry, and of citizenry. The most diverse city in the country (Cima 2014), Oakland is home to all types of people from every imaginable background each adding to the city’s vibrant culture. However, this racial and cultural diversity comes at the price of severe inequality of opportunity. Oakland is geographically segregated by ‘hills’ and ‘flatlands’, by haves and have-nots, and by racial majority and minority; its public school district eerily mirroring each of these dichotomies. Though the city’s population is almost exactly one quarter each white, black, and Latino (Oakland Fund for Children and Youth 2011; United States Census Bureau 2015), neighborhood schools in Oakland’s poorer neighborhoods are overwhelmingly filled with minority students trapped in what many describe as a failing system. Marred by low test scores and graduation rates averaging only 62.6%, the Oakland Unified School District or OUSD (Legislative Analyst’s Office 2013) reproduces existing inequalities based on race. And, like many districts across the country, unknowingly or otherwise, the system uses special education status to label those who do not conform behaviorally, ultimately delegating disproportionate numbers of black students into segregated educational programs and the school-to-prison pipeline that ensues (Hartrup 2015; Hing 2014).

In order to fully understand the current state of special education in Oakland and how it affects the city’s youth, it is necessary to take a step back and address the progression of federal policies surrounding education of the United States’ disabled populations. The conversation on special education began decades ago with a disagreement between two major schools of thought: separation and integration. Those who argued for segregation of students diagnosed with special needs believed that students with disabilities (SWDs) would thrive “in a more sheltered, protective environment wherein specialized services could be concentrated to meet their needs” (Sailor and McCart 2014:56). Additionally, proponents assumed, integration of students would require the classroom teacher to spend too much time with special needs students, thus taking time away from the ‘normal’ kids. On the other hand, however, students with disabilities may benefit from the chance to associate and spend time with general education students. This interaction, integrationists believe, promotes behavioral and social skills, and decreases the child’s feeling of marginalization. It is this last point that is possibly the most informative, as students who are diagnosed as special needs and then isolated from their peers may carry this label with them throughout life potentially causing decreased educational and social outcomes (Sailor and McCort 2014; Powell 2006).

These arguments culminated in the passing of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1990 (IDEA), modeled after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision (Hing 2014). Acknowledging that segregation of disabled students is inherently unequal, the act requires that all children receive education in the “least restrictive environment” (Sailor and McCort 2014:56) for their individual diagnosis ranging from complete segregation in off-site schools to integration within a general education classroom. However, as discussed later, racial segregation continued to be a hallmark of the special education system despite the reform’s roots racial desegregation legislation.

This new regulation requires that all students be provided with free appropriate public education and an Individualized Education Plan to outline specific requirements. In order to gain access to any of the resources promised under IDEA, however, multiple strategies must first be attempted within the general education framework including student study teams and response to intervention tactics. Upon the failure of these more modest interventions, the child is diagnosed with a disability that must “interfere with their educational attainment” (Legislative Analyst’s Office 2013). Once it is determined that a student requires an IEP, family members, teachers, and administrators get together annually to determine measurable goals for the year, an understanding of how these goals will be measured, and the extent to which the child will be included in mainstream education (Legislative Analyst’s Office 2013).

Though education for students with disabilities has arguably improved dramatically since the implementation of IDEA, all students are not treated as equal throughout the process. While racial differences in diagnosis are virtually non-existent for medical classifications such as hearing or visual impairments and brain injury, “soft disabilities” such as emotional and behavioral disturbances and learning disabilities are subjectively diagnosed and result in enormous racial disparities. Over diagnosis of students of color as special needs not only impacts their educational environment and outcome, but this designation is also understood as “a primary entry point into what’s been called the school-to-prison pipeline” (Hing 2014). As both racial minority and SPED diagnosis statuses are correlated with increased disciplinary action rates (U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights 2014), this pipeline serves to take students of color out of educational environments and funnel them into the criminal justice system through suspensions and expulsions.

These suspensions are significant even beyond the classroom time lost (which can be very detrimental on its own), as even just one suspension in the first year of high school doubles a student’s chances of dropping out before graduation. And though suspensions have not been found to rectify behavior within the classroom, they do serve to place already disadvantaged populations of students on a pathway leading out of the classroom and straight into the arms of the juvenile or adult criminal justice systems. As disciplinary practices can be so instrumental in determining a student’s future, it is imperative to understand this racial disparity in cities such as Oakland, California. Of the almost 50,000 students educated by the OUSD, 5,000 are enrolled in special education, and 80% of this group are either black or Latino (Oakland Fund for Children and Youth 2011). In a city where there are roughly equal populations of whites, blacks, and Latinos, these thoroughly unequal rates of minority students in special education is extremely problematic.

With the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, students diagnosed with special needs are required to receive an education that will help them succeed in their adult lives. However, this operates on the assumption that a diagnosis of disability is beneficial for the student. On the contrary, special needs status can lead to a segregated education, lower academic achievement, higher risk of entrance into the juvenile criminal justice system, lower rates of high school graduation, and decreased chance of continuing on to higher education (Artiles 2013:333). Nowhere may this intersection of race and special education be more important to understand than in Oakland, California where misdiagnosis due to cultural misunderstandings, traumas outside the classroom, and implicit racial biases can have life-long implications for the city’s minority youth. Though there have been many newspaper articles published which discuss the strong presence of the school-to-prison pipeline in Oakland (Bridges 2014; Hellmann & Martinez 2013), no academic research has empirically evaluated minority overrepresentation of SPED diagnosis there. This paper seeks to understand the link between the minority identities of race and special needs status within the context of the country’s most racially diverse city (Cima 2014).

LITERATURE REVIEW

Overrepresentation of Minority Students in Special Education:

There has been substantial research conducted on disproportionate identification of racial minority students as special needs, leading to a “’double bind’ that further compounds the structural disadvantages that each group has historically endured” (Artiles 2013:330). African-American students are three times more likely to have an intellectual disability diagnosis and two times more likely to have a diagnosis of emotional or behavioral disorder than their white peers (Artiles 2013: 330). These differences persist even after controlling for possible compounding factors such as poverty, and have serious consequences for the students in question.

However, there is little consensus within the literature as to exactly why this overrepresentation is so widespread. Ferri and Connor present special education as “racial segregation under the guise of disability” (2005b: 454); arguing that as racial segregation in schools became illegal with the passage of Brown v. Board of Education, special needs diagnosis took its place. The language of the “least restrictive environment”, they say, is now used as a loophole to recreate pre-Brown style segregation as white students labeled with special needs receive more in-class support, and minority students are more likely to be pulled out of the general classroom. Special education legislation, therefore, is a lawful way to distinguish and separate students of color, using “perceived academic difference as a justification for racial segregation and exclusion” (Ferri and Connor 2005a: 99). In this way, Ferri and Connor argue, the result of IDEA has ultimately been to enhance the failures of Brown v. Board. Sixty years after this landmark case, America’s schools are still extraordinarily racially segregated, and these authors see special education legislation as furthering the segregationist agenda. As Artiles argues (2013), only by understanding how race and ability function together in this way can scholars and citizens alike comprehend the current state of segregation in public schools (Ferri and Connor 2005b; Carrier 1986).

An analysis of the intersection of race and ability would not be sufficient, however, without a concrete understanding of the process through which minority students become overrepresented in special education and scholars have identified three potential causes of this disproportionality. As teacher referral is usually the first step in the diagnostic process, biases on the part of educators is perhaps the most influential factor in the staggering percentages of minority students in special education. Though nationwide 40% of public school students identify as a racial minority, 90% of public school teachers are white (Delpit 1995). Through no fault of their own, the vast majority of teachers are therefore stepping into racially and culturally diverse classrooms bringing, for the most part, white, middle-class values that they expect their students to adhere to. Though we assume no intentional bias on the part of teachers (this may not always be the case), referrals for special education testing reflect inadvertent racial discrimination as minority students are at “risk having their differences pathologized when measured against exclusionary, ethnocentric norms and standards” (Ferri and Connor 2005a: 94). It comes at no surprise, therefore, that the most subjective disability diagnoses are also those with the highest rates of minority overrepresentation (Ferri and Connor 2005a; Togut 2011).

Once a referral has been made for special education, the child is given multiple tests to determine if a diagnosis is appropriate. Depending on the student’s individual situation and suspected diagnosis, tests may include cognitive, social/emotional, adaptive behavioral, educational, and developmental assessments, as well as specific specialty area testing (School Psychologist Files 2015). However, like teachers’ expectations about classroom behavior, this type of testing utilizes supposedly universal assumptions that are actually highly variant. Based on family, cultural, and racial backgrounds these tests reflect white values, further disadvantaging the minority student and increasing their chances of identification as special needs. Paired with input from teachers (itself highly subjective), testing may exacerbate an incorrect identification of behavior as disability rather than cultural difference. This can result in the diagnosis of a minority student on the basis of classroom behaviors, the exact same of which may not have produced a diagnosis for a white student (Coutinho, Oswald, and Best 2002).

Finally, researchers cite sociodemographic factors as influencing the diagnosis of special needs within the minority student population. As race and class are so intertwined in the United States, some researchers assume that racial overrepresentation in special education is actually a byproduct of poverty, however Skiba, Poloni-Staudinger, Simmons, Feggins-Azziz, and Chung (2005) found this might not actually be the case. Their study looked at special education enrollment by race, socioeconomic status, and educational outcomes, and found that though poverty enhances the disproportionate levels of special needs diagnoses amongst minority students, it does not serve as a proxy for race. Even after controlling for poverty, African-American students in their sample were 2.5 times more likely to be diagnosed with mild mental retardation and 1.5 times more likely to be labeled as moderately mentally retarded than white students. Race, therefore seems to be an even stronger predictor of special needs identification than poverty, though the latter serves to “magnify already existing racial disparities” (Skiba et al. 2005: 141). A focus on poverty, the authors argue, may actually prevent other factors such as race from entering into discussions about overrepresentation and hide the educational structural inequalities that replicate existing racial hierarchies.

Overrepresentation does not occur at the same rate across all educational environments. Particularly, scholars have found that factors such as percent of minority versus white students in a school district can effect how pervasive the disproportionate identification of special needs is. Valenzuela, Copeland, Qi, and Park (2006) examined patterns of overrepresentation and discovered that identification of black students as special needs is negatively correlated with the proportion of black students in a school district. The fewer black students there are in a district, the more disproportionality exists within identification of special needs and, conversely, areas with higher populations of racial minorities demonstrate less overrepresentation. Togut (2011) corroborated these findings, discovering that whiter school districts had higher percentages of non-white students in special education than school districts with more equal numbers of minority and majority students. He posits that this could occur because white school districts have higher educational standards (possibly because of societal assumptions about the academic inferiority of minority students discussed above) and teachers then blame minority students for failing in school. Therefore, it is not only a student’s individual characteristics, like gender and ethnicity, but also the characteristics of their community, like poverty and racial diversity, that affect the likelihood of a disability diagnosis (Coutinho, Oswald, & Best 2002). It could be hypothesized that a more racially diverse city or school district may support less racial bias in special education identification, and this suggestion will serve as the entry point for my analysis of Oakland’s special education system later in this paper.

Potential Outcomes of Overrepresentation:

Before diving into Oakland as a case study for disproportionate identification of minority students as special needs, I must make clear the repercussions of these racially biased decisions. Not only do teacher expectations play a potential role in identification of students with disabilities, but once diagnosed, students with both racial minority and special needs status characteristics may derive lower expectations of success from general and SPED teachers alike (Ferri and Connor 2005a). Special needs identification also increases a student’s chances of dropping out of high school without the diploma so badly needed for college admission and entry into many careers, thus affecting these students’ potential future earnings (Ferri and Connor 2005a). More immediately, however, are the effects of a diagnosis on a child’s education while within the public school system. According to Valenzuela, Copeland, Qi, and Park, identification of the least restrictive environment depends on a child’s race, and African-American students with special needs are far more likely to be placed in the most segregated educational option of over 60% of time spent outside the general classroom (Valenzuela et al. 2006; Hosp and Reschly 2001). Denied access to the general education curriculum, students who may or may not be in need of special needs services are thus often relegated to segregated educational environments for the remainder of their K-12th grade educational careers.

Arguably the most detrimental outcome for minority students with convergent special needs identifications surrounds disciplinary action within the school (suspension and expulsion) and arrests made on school grounds. Looking at race alone, of the three million students in United States’ public school system, the vast majority of the 100,000 suspended are black (Hing 2014). And according to Togut (2011), black students (even those without a disability diagnosis) “are referred for discipline and subjected to harsher consequences for less serious behavior and for more subjective reasons” (Togut 2011:177) than their white counterparts. In fact, black students are upwards of three times more likely to be suspended or expelled as their white peers after exhibition of the same or similar behavior (Hartrup 2015; Moore 2015). This racial disparity is immensely consequential and begins before a child enters Kindergarten. According to the United States Department of Education Office for Civil Rights (2014), though only 18% of enrolled preschoolers are black, 48% of all suspensions in preschool are for black students. And, during their time from Kindergarten through high school, 16% of all black students serve at least one suspension compared to only 5% of white students.

Students with disabilities (majority and minority alike) are also more likely receive disciplinary action. The U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights (2014) reports that those with identified special needs are two times as likely to receive an out-of-school suspension than those without, as 13% percent of students with disabilities and only 6% of those without receive suspensions each year. However the greatest disparities in disciplinary action levels occur at the intersection of racial minority and disability identities. In the 2011-2012 academic year, 25% of black boys with disabilities nationwide faced suspension compared to 12% of disabled white boys and 10% of Asian boys with special needs status (Hing 2014): a concrete representation of Artiles’ concept of the “double bind” (2013).

School-to-Prison Pipeline:

Race and ability-based discrepancies in school disciplinary policies can result in overrepresentation of minority and SWDs in rates of suspension and expulsion, and the presence of the formal criminal justice system exacerbates this problem. According to a report by a coalition of the Black Organizing Project, Public Counsel, and the ACLU of Northern California, (2013) black students made up 73% of school police arrests in Oakland in the 2011-2012 academic year, despite comprising only 30.5% of the school district population. These organizations conclude that police arrests on school campuses are the main factor in the disproportionate high school drop out rates for minority students and raise questions about the efficacy of school arrest policies. Just as teacher bias can play a role in disproportionate referral of minority students for special needs testing due to differences in culturally-appropriate behavior, advocates like Kate Weisburd, attorney with the East Bay Community Law Center’s Youth Defender Project, worry that police arrests represent “the criminalization of childhood poverty and instability” (Hellmann and Martinez 2013).

Outcomes for the 85 students arrested in Oakland between 2010 and 2012 (zero of which were white) are pronounced. Even those that do not result in a conviction appear on a youth’s arrest record, which is not automatically sealed without a judicial order. For the 43 students whose arrests were sustained, however, consequences can be dire as their probation may be broken for simply being tardy to school or receiving poor grades. And once entered into the juvenile justice system, it is hard to escape, as recidivism rates are so high. Of those in Alameda County’s juvenile hall, a full 2/3 are returning inmates (Hellmann and Martinez 2013). And, as students with disabilities represent a full quarter of those arrested (despite comprising only 12% of public school populations) both black students and those with special needs enter into the criminal justice system at rates double that of peers without either of these disadvantaging characteristics (U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights 2014). Thus, minority and disabled students are disproportionately pushed out of the classroom and into educational segregation, are subjected to harsher disciplinary proceedings within school, and are more likely to come in contact with the criminal justice system. This problematic sequence “from frustrated, difficult kid to disabled, segregated student” (Hing 2014) completes the school-to-prison pipeline and serves to criminalize behaviors of those at the intersection of race and disability identities.

METHODOLOGY

In order to grasp the current state of racial bias in special education and its consequences in Oakland, California, I examine overrepresentation of minority students in the diagnosis of special needs. Next, I connect the disproportionate representation of both racial minority and special education students in disciplinary practices, and potential other biases these groups endure, before recognizing the ‘double-bind’ (Artiles 2013), which occurs at the intersection of both identities. Finally, I assess the potential outcomes of these types of misrepresentation, culminating with an investigation of the school-to-prison pipeline. Each of these literature reviews were conducted through thorough research using Google Scholar, Wesleyan databases, and searches of reputable newspapers and online magazines.

To ground my literature review in empirical data, I will examine records from the California Department of Education (2013) and the United States Census Bureau (2015a; 2015b). By analyzing rates of diagnosis of intellectual disability, emotional disturbance, and specific learning disability in Oakland and California, I will draw conclusions about one of the proposed factors of overrepresentation, namely the role of a city’s racial diversity in disproportionate representation in disability diagnosis. Specific definitions of each of these three disability diagnoses will be discussed, as well as statistics on Oakland as the context for my research before any data analysis is conducted.

DEFINITIONS

Intellectual Disability

Intellectual disabilities, referred to as ‘mental retardation’ until the 2010 passage of ‘Rosa’s Law’, are defined by the presence of three criteria. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual V, which is used in the diagnosis of all psychological impairments, a child must present “deficits in general mental abilities such as reasoning, problem-solving, planning, abstract thinking, judgment, academic learning, and learning from experience”, usually corresponding to an IQ of 70 or below to be considered for diagnosis of intellectual disability. Additionally, these deficits have to restrict the child’s ability to function in comparison to others of their “age and cultural group by limiting and restricting participation and performance” in activities such as communicating with others, playing, functioning at school or at work, and living independently. Finally, these insufficiencies must emerge during the period of development. The World Health Organization and Individuals with Disabilities Education Act define intellectual disabilities similarly, with the former citing “arrested or incomplete development of the mind… characterized by impairment of skills that contribute to the overall level of intelligence” (Brock 2012). IDEA itself requires “significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning, existing concurrently with deficits in adaptive behavior and manifested during the developmental period, that adversely affects a child’s educational performance” (Brock 2012; U.S. Department of Education 2004).

Emotional Disturbance

Criteria for the diagnosis of emotional disturbance is much more lenient and open to subjective interpretation than that of intellectual disability. According to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, in order to obtain this diagnosis, a child must display only one of the following characteristics over time and to a degree that interferes with academic achievement (Center for Effective Collaboration and Practice 2001).

- “an inability to learn that cannot be explained by intellectual, sensory, or health factors”

- “an inability to build or maintain satisfactory interpersonal relationships with peers and teachers”

- “inappropriate types of behavior or feelings under normal circumstances”

- “a general pervasive mood of unhappiness or depression”

- “a tendency to develop physical symptoms of fears associated with personal or school problems”

As an individual only must display one of these symptoms, and many overlap with other diagnoses, identification is extremely subjective. Criteria such as difficulty developing healthy relationships with peers and teachers, and depressed behavior may, in some cases, not be a disability per se, but rather the result of bias in the diagnostic process or other unrelated factors. Implicit or explicit, biases on the part of teachers and school administrators, as well as cultural stereotypes about black males, may interfere with objective definitions of students with a potential emotional disturbance diagnosis. This subjectivity may very well be a causal factor in disproportionate representation, as in the 2011-2012 year, black students were twice as likely as Latino students and 1.4 times as likely as their white peers to be diagnosed as having an emotional disturbance disorder (Hing 2014). Additionally, many students with emotional disturbance have comorbid diagnoses such as mood, anxiety, conduct, and other psychiatric disorders, as well as Attention Deficit and Hyperactive Disorder or ADHD. All of these potential comorbidities (the presence of two or more diagnosed disorders) may intensify the impact that the initial emotional disturbance has on a child’s education (Center for Effective Collaboration and Practice 2001).

Specific Learning Disability

Specific Learning Disability is a sort of catch-all definition which encompasses any “disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understand or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations”. This definition, however, does not include problems that are “the result of visual, hearing, or motor disabilities, of mental retardation, of emotional disturbance, or of environmental, cultural, or economic disadvantage” (U.S. Department of Education 2004). Those who struggle with specific learning disabilities feel their reach in many aspects of life, as the diagnosis is associated with low self-esteem, teenage pregnancy, family problems, drug abuse, depression, and other psychological problems. It may come as no surprise then, that students with LDs are twice as likely as students without to drop out of high school. However, unlike physical disabilities, these are often considered “hidden handicaps” as they are difficult to identify. Some symptoms of LDs include inconsistent academic performance, distraction, trouble remembering material previously learned, reversal of numbers and letters, reading below grade level, confusion about directions and time, disorganization of personal life, impulsive or inappropriate behavior, difficulty following directions, and below average motor coordination (Learning Disabilities Associate of California 2015). Like the emotional disturbance diagnosis, however, these symptoms are often characteristic of other, potentially unrelated problems, which complicate the diagnostic process.

CONTEXT

Oakland, California is located across the bay from San Francisco. An important shipping port and the endpoint for three transcontinental railroads, the city’s population has grown steadily since its incorporation in 1854 (Infoplease). The population of this mid-sized city is remarkable in its outstanding racial diversity, represented in Figure 1. Oakland’s public schools, however, do not portray proportionate levels of Black, White, and Latino students. (See Table 1 for Oakland Unified School District enrollment breakdown by race.) The difference between the city’s racial breakdown and that of the public school system may be explained by a proportion of white families choosing alternative options for education including private and parochial schools. Nonetheless, this extreme racial range both in overall population and that of children enrolled in public schools makes Oakland, by some calculations, the most diverse city in the country, offering a unique case study of disability diagnosis in a racially diverse context (Cima 2014).

DATA ANALYSIS

Using data from the U.S. Census Bureau (2015a; 2015b) and California Department of Education (2013), I have drawn conclusions about the state of racial overrepresentation in special education diagnosis, as well as the effect of a community’s racial diversity on differential patterns of diagnosis. For this analysis, I will focus on black, Hispanic, and white students. These three major ethnic groups were chosen for analysis because literature on special education diagnosis suggests that black students are the most overrepresented, Hispanic students serve as another minority group against which I can compare levels of black student identification, and white students represent the ethnic “majority” (though the white population is not the majority in Oakland). A fourth ethnic group, Asian, is included to show overall racial breakdown by city and state but is not included in data on special education enrollment.

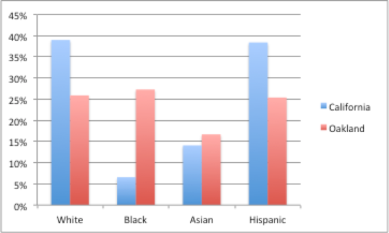

Figure 1 represents percentages of each of the four major ethnic groups in the state of California and the city of Oakland. As discussed earlier, Oakland’s population is almost exactly one quarter each white, black, and Hispanic. California as a whole, on the other hand, has a population of almost equal parts white and Hispanic, but a much smaller black population. It can be inferred from this data that Oakland is much more racially diverse than the state of California in terms of equally balanced racial groups in the population (United States Census Bureau 2015a; United States Census Bureau 2015b).

Figure 1: Oakland and California Populations by Major Ethnic Group (U.S. Census Bureau)

Analysis of diagnostic patterns of enrollment, however, must be conducted based on OUSD enrollment rather than Oakland’s general population. As discussed previously, though roughly one quarter of Oakland’s population is white, only 9.79% of enrolled OUSD students are white. And while percentage of black students roughly mirrors percentage of Oakland’s population that is black, Hispanic students represent a far larger proportion of public school enrollment than the general population (California Department of Education 2013).

Table 1: OUSD Enrollment by Ethnicity (California Department of Education 2013)

| Asian | Hispanic | Black | White | Other | Total |

| 6,230 | 20,149 | 13,222 | 4,621 | 2,972 | 47,194 |

| 13.2% | 42.69% | 28.02% | 9.79% | 6.3% | 100% |

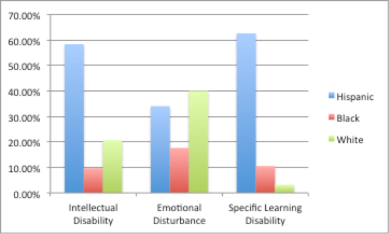

Figure 2 plots OUSD special needs enrollment by major racial group as a percent of total enrollment within each disability category. Confirming literature on overrepresentation of black students in disability diagnosis, though 28.02% of Oakland’s students are black, they comprise 46.34% of intellectual disability, 64.20% of emotional disturbance, and 46.65% of specific learning disability diagnosis. The opposite trend is seen for both Hispanic and white students. Hispanic students are 42.69% of OUSD’s student population, but only 38.28% of intellectual disability, 26.33% of emotional disturbance, and 37.57% of specific learning disability diagnosis. Similarly, white students are 9.79% of the total student body, but account for only 2.93%, 5.62%, and 5.51% of intellectual disability, emotional disturbance, and specific learning disability diagnoses, respectively. In Oakland, Hispanic and white students are therefore underrepresented in special education enrollment, while black students are overrepresented in each of the disability categories analyzed by this research (California Department of Education 2013).

Figure 2: OUSD Disability by Ethnicity: percent of total within disability

The same sorts of analysis can be performed using data from the entire state. As compared to the total state population, there are fewer white and Asian students in California’s public schools, suggesting a portion of these students are educated elsewhere. The percentage of black students in CA schools is roughly the same as percentage of black residents in the state, but a far higher percentage of California public school students are Hispanic than the general population (53.25% of students and 38.4% of California total population is Hispanic).

Table 2: California Public Schools Enrollment by Ethnicity (Population and Percentage)

| Asian | Hispanic | Black | White | Other | Total |

| 542,540 | 3,321,274 | 384,291 | 1,559,113 | 429,454 | 6,236,672 |

| 8.70% | 53.25% | 6.16% | 25.00% | 6.89% | 100% |

Like Oakland, California as a whole demonstrates patterns of overrepresentation of minority students in special needs enrollment. Though black students only make up 6.16% of CA school population, they represent 9.7% of intellectual disability, 17.66% of emotional disturbance, and 10.54% of specific learning disability diagnoses. Hispanic students are also slightly overrepresented in diagnosis, as they constitute 58.38% of intellectual disability and 62.62% of learning disability diagnoses, despite comprising 53.25% of school population. Surprisingly, according to this data, white students demonstrate severe overrepresentation in emotional disturbance diagnosis, making up 40.02% of identifications for this disability, despite being 25.00% of CA public school enrollment. In the other two diagnosis categories, however, white students are underrepresented, as are Hispanic students for emotional disturbance (California Department of Education 2013).

Figure 3: California Disability by Ethnicity: percent total within disability

Across both geographic areas and all three disabilities highlighted for this research, there is overrepresentation of black students in SPED enrollment. Disproportionately high rates of identification also occur in California for Hispanic and white students in certain diagnostic categories (intellectual and learning disabilities for Hispanic students and emotional disturbance for white students). However, these figures of slight overrepresentation for the latter two ethnic groups do not represent a serious pattern. This data demonstrates that perhaps it is not minority students in general that are over-diagnosed for SPED, but black students specifically, suggesting that there may be something fundamentally different about the experiences of black and Hispanic minority populations in special needs identification.

CONCLUSION

Analysis of data from the California Department of Education has allowed me to confirm certain aspects of overrepresentation, disciplinary, and criminal justice theories regarding racially disproportionate diagnosis of special needs. As data on the diagnosis of intellectual disabilities, emotional disturbance, and specific learning disabilities suggest, both California and Oakland public schools are sites of race-based differential diagnosis patterns. It can be concluded from this analysis that overrepresentation of black students does occur in public schools both statewide and in Oakland.

This result may be somewhat surprising given Oakland’s extraordinary level of racial diversity as nowhere else in the country are four major racial groups (Hispanic, African-American, White, and Asian) as equally represented in the population. This racial diversity, according to both Valenzuela et al. (2006) and Togut (2011), should result in decreased levels of overrepresentation of minority students in SPED. However, my analysis does not confirm the theory that areas with a higher percentage of minority populations display less disproportionate identification in rates of diagnosis. Rather, as compared to California, which is less racially diverse, Oakland had equal, if not higher, levels of disproportionate diagnosis for black students.

This confirmation of overrepresentation of minority students in SPED diagnosis in the diverse setting of Oakland, California highlights the importance of policy changes to ensure children of color and special needs are not funneled through the school-to-prison pipeline. Oakland has recently taken steps to decrease the reach of the formal criminal justice system by ensuring that parents are notified before their child can be interviewed by police, engaging in alternative disciplinary actions within the school such as restorative justice, and better tracking arrests within schools, paying specific attention to arrest rates of African-American students (Bridges 2014). However, these policies ignore the intensification of the school-to-prison pipeline for students also diagnosed as special needs. As special education serves to further segregate minority students and increases a youth’s chances of being suspended, expelled, or arrested, Oakland and other cities must include this identity in their analysis of the overrepresentation of black students caught in the school-to-prison pipeline.

Though this research acts as a case study of special education identification in an exceptionally diverse American city, it lacks an in-depth understanding of the experiences of individual students or schools in Oakland. Without access to data regarding SPED populations in individual schools in the district, I was unable to analyze potentially significant differences in overrepresentation rates amongst Oakland’s public schools. This type of information may have yielded interesting results, given the vast differences between schools in the Oakland Hills and those in the ‘flatlands’ of East and West Oakland. Additionally, this study could have been augmented by ethnographic research within the OUSD. More accurate information regarding the outcomes of disproportionate identification, including access to general curriculum, access to SPED resources, and suspension and arrest rates, may have been useful and could have been gleaned through interviews with students, parents, and teachers within the system. However, data presented by the California Department of Education was sufficient for a broad analysis of patterns of overrepresentation of minority students in the diagnoses of intellectual disabilities, emotional disturbance, and specific learning disabilities.

Literature on special education diagnosis and the inequalities it reinforces is widespread. Careful data analysis and theoretical insight offers important evidence of the outcome of a federal policy designed to assist an underserved segment of the American population, and helps to unmask the nearly invisible inner workings of subjective disability diagnosis within school systems. However, the realities of these diagnoses – the actual educational, social, and civil outcomes – had yet to be studied in the context of Oakland, which, according to prominent scholars, may have the best chance of any city to overcome minority overrepresentation in SPED diagnosis. Unfortunately, this does not seem to be the case. Oakland’s diverse population has not successfully combated disproportionate disability diagnosis of racial minority students; rather it serves as yet another example of the ultimate failure of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

Though IDEA has allowed some students access to resources previously denied to them, it has also permitted the legal segregation of students based on ability. This separation has culminated either accidentally or purposefully (according to some scholars) in the designation of high proportions of minority students to subpar educational environments and increased contact with the criminal justice system. Although I would not argue, nor I presume would many of the aforementioned scholars, that the state of affairs pre-IDEA should be regarded as superior to our current system, it is clear that changes must be made. First and foremost, those in the academic community must become more aware of implicit biases and assumptions that negatively impact both students of color and students with disabilities. Then, we must thoroughly comprehend the experience of those at the intersection of these identities, and work to rectify a system of identification that has been proven, time and time again, to act in disservice to the students in question.

WORKS CITED

Artiles, Alfredo J. 2013. “Untangling the Racialization of Disabilities.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race10(2):329-347

Black Organizing Project, Public Counsel, and the ACLU of Northern California. 2013. From Report Card to Criminal Record: The Impact of Policing Oakland Youth. Oakland, CA: BOP, Public Counsel, and ACLU

Bridges, Christopher. 2014. “Oakland Unified School District Takes Steps to End School-to-Prison-Pipeline.” American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California. Retrieved April 21, 2015 (https://www.aclunc.org/blog/oakland-unified-school-district-takes-steps-end-school-prison-pipeline).

Brock, Stephen E. 2012. Identifying Intellectual Disability: Guidance for the School Psychologist. California State University, Sacramento. Sacramento, CA: Sacramento State. Retrieved April 15, 2015 (http://www.csus.edu/indiv/b/brocks/workshops/casp/brock.ws03.id.pdf).

California Department of Education. 2013. DataQuest. California Department of Education. Sacramento, CA. Retrieved February 28, 015 (http://data1.cde.ca.gov/dataquest/)

Carrier, James G. 1986. “Sociology and Special Education: Differentiation and Allocation in Mass Education.” American Journal of Education 94(3):281-312

Center for Effective Collaboration and Practice. 2001. “Eligibility for Services.” Retrieved April 14, 2015 (http://cecp.air.org/resources/20th/eligchar.asp).

Cima, Rosie. 2014. “The Most and Least Diverse Cities in America.” Retrieved March 29, 2015 (http://priceonomics.com/the-most-and-least-diverse-cities-in-america/)

Coutinho, Martha J., Donald P. Oswald, and Al M. Best. 2002. “The Influence of Sociodemographics and Gender on the Disproportionate Identification of Minority Students as Having Learning Disabilities.” Remedial and Special Education 23 (1): 49-59

de Valenzuela, J. S., Susan R. Copeland, and Cathy Huanqing Qi. 2006. “Examining Educational Equity: Revisiting the Disproportionate Representation of Minority Students in Special Education.” Exceptional Children 72 (4): 425-441

Delpit, Lisa. 1995. Other People’s Children: Cultural Conflict in the Classroom. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co.

Ferri, Beth A., and David J. Connor. 2005a. “In the Shadow of Brown: Special Education and Overrepresentation of Students of Color.” Remedial and Special Education 26 (2): 93-100

Ferri, Beth A., and David J. Connor. 2005b. “Tools of Exclusion: Race, Disability, and (Re)segregated Education.” Teachers College Record 107 (3): 453-474

Hartrup, Molly. 2015. “Battling the School-to-prison Pipeline.” Illinois State University, February 24. Retrieved February 28, 2015 (http://stories.illinoisstate.edu/university/media-relations/battling-school-prison-pipeline/).

Hellmann, Melissa., and Yolanda Martinez. 2013. “Breaking the School-to-Prison Pipeline: Examining Arrests Among Black Male Students in OUSD.” Retrieved March 29, 2015 (https://oaklandnorth.net/2013/12/11/breaking-the-school-to-prison-pipeline-examining-arrests-among-black-male-students-in-ousd/).

Hing, Julianne. 2014. “Race, Disability and the School-to-Prison Pipeline.” Color Lines News for Action. May 13. Retrieved February 28, 2015 (http://colorlines.com/archives/2014/05/race_disability_and_the_school_to_prison_pipeline.html).

Hosp, John L., and Daniel J. Reschly. 2001. “Predictors of Restrictiveness of Placement for African-American and Caucasian Students.” Exceptional Children 68 (2): 225-238

Infoplease. 2007. “Oakland, Calif.” Retrieved April 15, 2015 (http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0108573.html).

Learning Disabilities Association of California. 2015. “What is LD?”. Retrieved April 15, 2015 (http://www.ldaca.org/learning-disabilities.php).

Legislative Analyst’s Office. 2013. Overview of Special Education in California: Executive Summary. Sacramento, CA: Legislative Analyst’s Office

Moore, Shasta Kearns. 2015 “PPS Plan Would Integrate Special Ed” Portland Tribune, January 15. http://portlandtribune.com/pt/9-news/246924-114159-pps-plan-would-integrate-special-ed

Oakland Fund for Children and Youth. 2011. Oakland Youth Indicator Report: OFCY 2013-2016 Strategic Planning. Oakland, CA: Oakland Fund for Children and Youth

Oakland Unified School District. 2013. Fast Facts (2012-13). Oakland, CA: Oakland Unified School District

Powell, Justin J. W. 2006. “Special Education and the Risk of Becoming Less Educated.” European Societies 8(4):577-599

Sailor, Wayne., and Amy B. McCart. 2014. “Stars in Alignment.” Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 39 (1): 55-64

School Psychologist Files. 2015. “Special Education Testing.” Retrieved April 19, 2015 (http://schoolpsychologistfiles.com/spedtesting/).

Skiba, Russell J., Lori Poloni-Staudinger, Ada B. Simmons, L. Renae Feggins-Azziz, and Choong-Geun Chung. 2005. “Unproven Links: Can Poverty Explain Ethnic Disproportionality in Special Education?” The Journal of Special Education 39 (3): 130-144

Togut, Torin D. 2011. “The Gestalt of the School-to-Prison Pipeline: The Duality of Overrepresentation of Minorities in Special Education and Racial Disparity in School Discipline on Minorities.” Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law 20 (1): 163-181

United States Census Bureau. 2015a. State & County QuickFacts: California. United States Census Bureau. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved April 15, 2015 (http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06000.html)

United States Census Bureau. 2015b. State & County QuickFacts: Oakland (city), California. United States Census Bureau. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved April 15, 2015 (http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06/0653000.html).

U.S. Department of Education. 2004. “Building the Legacy: IDEA 2004.” Retrieved April 15, 2015 (http://idea.ed.gov/explore/view/p/,root,regs,300,A,300%252E8,).

United States Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. 2014. Civil Rights Data Collection, Data Snapshot: School Discipline. (Issue Brief No. 1). Washington, DC: United States Department of Education

This was a very thought provoking article that I plan to share with my university freshman honors students in a course, Diability and Inclusion in a Diverse Society. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your comment and I’m glad you enjoyed the paper! I’m happy to hear you’ll be able to use it. Feel free to comment if you have any questions or further reactions.

LikeLike

This is a wonderful article, would it be okay if I use it as part of my university course work?

LikeLike

Yes, definitely! Please just cite my work in your paper.

LikeLike

Of course. It’s for a PhD paper I am writing in sig dig in sped and I am from northern CA so it’s perfect!! Thank you!!!

LikeLike